(Course) LCA Practice & Reporting 21-22

Jeroen Guinee and Bernhard Steubing

Intensive theory week (5 days; 9 to 5)

Table of Contents

2122-S1 LCA Practice & Reporting - Theory Week: Lectures

1. Introduction LCA-PR

Overall aim: provide sufficient scientific basis and practical skills to perform an attributional life cycle assessment (ALCA) study.

• Draft a concise, to-the-point proposal for their own LCA research including a brief

literature review

• Perform a methodologically consistent and proper LCA study

• Develop a proper LCA model in CMLCA

• Present results, identify problems and propose solutions

• Plan and monitor research

• Report an LCA study and its findings transparently and comprehensively

• Identify, justify and report LCA’s key methodological assumptions and choices

• Critically evaluate and discuss the possibilities and constraints of their LCA study.

Assignment 1: Research proposal

Proposals should demonstrate the environmental relevance of the chosen case study with existing literature as well as provide justification for the use of LCA in their specific applications. The goal of the research proposal is for students to formulate the research question (including a hot spot analysis), identify challenges and make a work plan.

Research proposal requirements and guidelines

As preparation for drafting the research proposal, students are required to read the article by Hengl and Gould (2002): https://www.itc.nl/library/papers/hengl_rules.pdf. Proposals are graded according to how well the student follows the requirements below.

Format and submission requirements

• Proposals must be submitted through Brightspace (Leiden) / Assignments (use the similarity check to resolve any outstanding issues prior to the due date).

• Max. 2000 words including a maximum 300 words abstract, Tables, Figures, frontpages, etc., while excluding only references and appendices.

Content requirements

• Title and student name

• Abstract (300 words): Define the research question(s), propose an LCA case study, describe the scope and discuss your approach. Tell us why the case study is important and why a life cycle approach is necessary. The abstract at this point should make your audience want to know more about your study without necessarily having the final results.

• Introduction (problem statement, literature review, research question, …. ): Include background information, previous research on the topic (including LCA literature). Here, you will use existing literature (at least 2 reference LCA studies) to construct the problem statement and identify a knowledge gap. For example, “all studies so far focus on the comparative advantages at the use phase, while neglecting manufacturing and processing which may not compensate for gains in efficiency. This study takes a life cycle approach to evaluate the systemic environmental implications of A and B and determine if there is an environmental advantage to either one. Moreover, hot spots are identified for both alternatives”.

• Goal and Scope Definition: Under goal definition include a brief discussion on goal, intended application of your study, researcher, commissioner, target audience, steeringcie, expert reviewer. Under scope definition include a brief discussion on ALCA/CLCA, detailed LCA, temporal/geographical/technology coverage, coverage of processes and of interventions and impacts. Finally, discuss function, FU, alternatives, and reference flows.

• Flowcharts: Preliminary flowcharts following the conventions learned during the Theory week (no copy from literature). One flow chart per alternative.

• Method: This section outlines how you will proceed with your LCA. This includes data collection (identified data sources), impact assessment families applied, recycling, and allocation.

• Fulfillment of model requirements (pg. 8). Discuss how you will meet the model requirements (see below under assignment 3).

• Discussion: Identify possible difficulties and their solutions. This is an opportunity to identify areas that may be challenging. Along with the challenges, try to propose a solution (even if it is too early) as you can get feedback on how you plan to proceed.

• Planning: Provide a schedule for the work plan. This should include all phases of LCA as presented during the Theory Week as well as the milestones (assignments) and possible periods that you will not be able to work on your case study.

• References: Use the format of the Journal of Industrial Ecology (Harvard style) to organize your references (https://jie.yale.edu/jie-style-guide-accepted-manuscripts) and/or use a reference manager using the correct (JIE) export settings or Word import settings. Include relevant and sufficient

Advice

Use the theory week to think, talk and discuss your ideas with the group;

Use the terminology you learned during the theory week (glossary);

Time is limited, focus on the course requirements and don’t set your additional requirements too high. For example, leave the “Life Cycle Stage contribution analysis” for the end.

While waiting for our feedback you can already start doing your research, use all the time you have.

Assignment 2: Presentation

Assignment 3: Final report

For the LCA-PR course the student is expected to perform a methodologically consistent and proper LCA case study based on what has been taught during the Theory Week. The student needs to submit a properly structured and type-written report, along with the CMLCA-file (‘model’) that is created for the LCA study. Through the report and the CMLCA-file, the student should convince the course instructors that (s)he understands the LCA theory, how to apply the theory in practice in a case study, and how to interpret an LCA study’s results taking into account the proper use and constraints of LCA.

The results of the case study performed during the course cannot generally classify as a full LCA. Instead, this is more of an educational exercise. Please have this in mind when performing your case study.

Model requirements (Mandatory!)

In addition to the use of the background ecoinvent v3.4 database, the student should model (in CMLCA) at least 5 foreground unit processes including:

• 1 disposal process (modelling waste flows out and not waste services (as goods) in!)1

• 1 closed-loop (reuse or closed-loop recycling);

• 1 multifunctional co-production process (not open-loop recycling, but co-production process!) (explicitly reporting on all 4 steps as learned during the Theory Week; see last slide of the Allocation presentation); applying two ways (of which one may be a sensitivity analysis) of allocation including economic allocation2;

• 1 unit process with at least 3 environmental emissions (extensions) calculated by the student3. Note that directly gathering values from literature does not count;

• at least (!) 1 additional unit process free of choice.

The closed loop process also needs allocation but this does NOT count as the multifunctional process at the same time, so you need to model these two processes separately.

Next to the modeling the work should also include a comparison of (at least) two product alternatives, a full impact assessment (not just a couple of impact categories) selecting two families (at least the PEF as baseline, and the CML or ReCiPe family as sensitivity analysis), at least two types of contribution analysis (applying the built-in functions of CMLCA, e.g., at the level of process contributions to category indicator results and at the level of process-emissions contributing to category indicator results for all impact categories, optionally grouping processes manually into stages (which is not the same as a contribution analysis by life cycle stage (LCS or ‘big ship’ analysis), etc.; applying the LCS (or ‘big ship’) contribution analysis is optional, not (!!) mandatory but can deliver extra points when properly performed) and several sensitivity analyses (at least three: one on allocation (see above), one on characterization families (see above); and one free choice, preferably based and justified by your contribution analysis results). Finally, the student should report in a short table how these model requirements have been dealt with in the report.

Reporting

Students should use the mandatory report lay-out presented below. Next to that the ISO 14040 guidelines should be followed to report the LCA work done. Additional guidance on reporting can be found in the Handbook on LCA, which includes elaborated reporting guidelines on the basis of these ISO reporting guidelines. It is strongly recommended to use the Handbook for this. The abstract should not exceed 300 words. The main report should not exceed 6000 words (no range; 6000 is the limit), including Tables, Figures, frontpages, etc., while excluding only references and appendices. but excluding references and supporting information. Any text beyond 6000 words will not be taken into account for grading, although appendix/appendices may be provided in which the student provides supporting information (no page limit). Don’t forget to insert page numbers in your report! Data reporting is crucial! Students should use the CMLCA unit process data format to present the data for their foreground processes, and in the main report and appendices (supporting information) they should clearly document how they got from the raw literature/internet data to the eventual unit process data implemented in their CMLCA file, including all assumptions, calculations and sources used.

Finally, you need to carefully think what to put in the main report with the word limit, and what to put in Appendices. You cannot “outsource” important information to the annexes. All important information needs to be in the main text, and appendices should be made for the inventory table, classification tables and further detailing of information (e.g., of process data) included in the main report. Teachers should be basically able to understand your case study, assumptions, data, results etc. by reading the main report only.

Mandatory report lay-out

All points below should be addressed in your final report. You can add other topics (for example, contribution analysis by life cycle phase and/or uncertainty analysis) but these need to be covered at the correct location in your report according to the ISO14040 structure and the LCA Handbook. Instructions on how to describe specific topics can be found in the LCA Handbook.

- Abstract (less than 300 words)

- Table of contents

- Course modelling requirements in a Table with process numbers and short explanation

- Introduction

- Goal and scope definition

a. Goal definition

b. Scope definition

c. Function, functional unit, alternatives, reference flows - Inventory Analysis

a. System boundaries:

i. Economy-environment system boundary

ii. Cut-off

b. Flowchart

c. Data collection and relating data to unit processes

d. Multi-functionality and allocation, report all 4 steps for all your foreground processes in the main report indicating the criterion used to determine between Goods and Wastes and summarizing the other 3 steps in, e.g., a table:

Don’t forget to add how you solved the multifunctionality of these processes and how you calculated the allocation factors and which data you used for that.

e. Results of inventory analysis (Inventory table in appendix and briefly discuss 2-3 examples) - Impact assessment

a. Impact categories, characterization models, category indicators, characterization factors (explain which family/-ies you chose and why, report briefly on related characterisation models, indicators and factors showing understanding)

b. Classification

c. Characterization results and discussion

d. Normalisation results and discussion

e. Interventions for which characterization factors are lacking (include as appendix and briefly discuss 2-3 examples)

f. Economic flows not followed to system boundary - Interpretation

a. Consistency check

b. Completeness check

c. Contribution analyses

d. Sensitivity analysis - Discussion

- Conclusions and recommendations

- References: Use the format of the Journal of Industrial Ecology (Harvard style) to organize your references (https://jie.yale.edu/jie-style-guide-accepted-manuscripts) and/or use a reference manager using the correct (JIE) export setting or Word import settings. Include relevant and sufficient references.

- Appendices / Supporting information

2. History of LCA

Life Cycle Assessment: Past, Present, and Future

Jeroen B. Guinée

Environ. Sci. Technol. September 2, 2010

- The study of environmental impacts of consumer products has a history that dates back to the 1960s and 1970s. Especially in a comparative context (“Is product A better than product B?”).

2.1 The Past of LCA (1970−2000)

1970−1990: Decades of Conception

- One of the first (unfortunately unpublished) studies quantifying the resource requirements, emission loadings, and waste flows of different beverage containers was conducted by Midwest Research Institute (MRI) for the Coca Cola Company in 1969.

- During the 1970s and the 1980s LCAs were performed using different methods and without a common theoretical framework. LCA was repeatedly applied by firms to substantiate market claims.

1990−2000: Decade of Standardization

- The period of 1990−2000 can therefore be characterized as a period of convergence through SETAC’s coordination (“Code of Practice”) and ISO’s standardization activities (1994)

- A key result of ISO’s standardization work has been the definition of a general methodological framework.

2.2 The Present of LCA: Decade of Elaboration

Diverging approaches have been developed with respect to system boundaries and allocation methods, dynamic LCA, spatially differentiated LCA, risk-based LCA, and environmental input-output based LCA (EIO-LCA) and hybrid LCA (69-71) that may have a tense relation with some of the basic principles of the ISO standards.

2.3 LCA Future (2010−2020): Decade of Life Cycle Sustainability Analysis

2.4 Discussion

3. Glossary, Flowchart, and Unit process

3.1 Glossary

From LCA Handbook (Guinée et al. 2002).

This glossary provides definitions of the key terms and abbreviations used in the MSc-IE LCAPR course. The glossary is copied from the LCA Handbook (Guinée et al. 2002). Terms marked with an asterisk (*) are defined in accordance with the definitions given in the ISO 1404X series of standards, although not necessarily according to the letter. For reasons explained in the LCA Handbook, several definitions adopted here deviate substantively from those of ISO. In this Glossary these are marked as “adapted from ISO”. Cross-references,

indicated by an arrow (→), point to the preferred terms used in the LCA Handbook.

Terms:

abiotic resource /ˌeɪbaɪ’ɒtɪk/:

a natural resource (including energy resources) regarded as non-living, e.g. zinc ore, crude oil, wind energy.

allocation

→ multifunctionality and allocation.

alternative

one of a set of product systems studied in a particular LCA, e.g. for comparison (note: some LCA steps are carried out for all alternatives together (e.g. selection of impact categories), while others are repeated for each alternative (e.g. characterisation).

area of protection

a cluster of category endpoints of recognisable value to society, viz. human health, natural resources, natural environment and man-made environment.

average modeling

→ proportional modeling.

background system/process

a system or process for which secondary data, viz. databases, public references, estimated data based on input-output analysis, are used in an LCA.

baseline method (model, impact category, LCA, etc.)

a method (etc.) recommended in this Guide for operationalising an LCA or methodological step.

biotic resource

a natural resource (including energy resources) regarded as living, e.g. rainforests, elephants.

casualty

human injury or death due to direct, physical cause, e.g. explosion or traffic collision (but not indirect casualties, e.g. due to toxics).

category endpoint\*

an attribute or aspect of the natural environment, human health, natural resources or the man-made environment identifying an issue of concern, e.g. loss of coral reefs or crops, damage to buildings.

category indicator\*

a quantifiable representation of an impact category, e.g. infrared radiative forcing for climate change

category indicator result\*

→ indicator result

cause-effect network

→ environmental mechanism

change-oriented LCA (consequential LCA (CLCA))

a type of LCA focusing on the environmental changes resulting from a switch to or from a particular product system or an extra functional unit of a particular product system.

characterisation\*

a step of Impact assessment, in which the environmental interventions assigned qualitatively to a particular impact category (in classification) are quantified in terms of a common unit for that category, allowing aggregation into a single score: the indicator result; these scores together constitute the environmental profile.

characterisation factor\*

a factor derived from a characterisation model for expressing a particular environmental intervention in terms of the common unit of the category indicator, e.g. POCPmethanol (photochemical ozone creation potential of methanol)

characterisation method

a method for quantifying the impact of environmental interventions with respect to a particular impact category; it comprises a category indicator, a characterisation model and characterisation factors derived from the model.

characterisation model

a mathematical model of the impact of environmental interventions with respect to a particular category indicator.

characterisation result

→ environmental profile

classification\*

a step of Impact assessment, in which environmental interventions are assigned to predefined impact categories on a purely qualitative basis.

closed loop recycling\*

recycling of material within one and the same product system.

combined waste processing

a method of waste processing in which more than one form of waste is processed simultaneously.

comparative assertion\*

an environmental claim regarding the superiority or equivalence of one product relative to a competing product performing the same function; particular requirements are set by ISO on comparative assertions disclosed to the public.

completeness check\*

a step of the Interpretation phase to verify whether the information yielded by the preceding phases is adequate for drawing conclusions in accordance with the Goal and scope definition

consistency check\*

a step of the Interpretation phase to verify whether assumptions, methods and data have been applied consistently throughout the study and in accordance with the Goal and scope definition.

contribution analysis\*

a step of the Interpretation phase to assess the contributions of individual life cycle stages, (groups of) processes, environmental interventions and indicator results to the overall LCA result (e.g. as a percentage).

co-product\*

any of two or more functional flows from a co-production process.

co-production process

a unit process having more than one functional flow, e.g. crude oil refining.

critical review\*

an expert (internal or external) review of an LCA, designed to ensure validity, consistency, transparency and credibility of results.

damage approach

definition of category indicators close to areas of protection.

data category\*

a heading for classifying data in an LCA, e.g. energy inputs, raw material inputs, ancillary inputs, other physical inputs, products, emissions to air, emissions to water, emissions to land, other environmental aspects.

data quality\*

a data characteristic relevant for the capacity of the data to satisfy stated requirements.

data quality requirements\*

specification, in general terms, of the quality criteria to be satisfied by the data used in an LCA.

depletion

a decrease in the stock of a biotic or abiotic resource due to extraction thereof.

descriptive LCA (attributional LCA (ALCA))

a type of LCA focusing on the contribution of a particular way of fulfilling a certain function to the entire spectrum of environmental problems as they currently exist or are being created.

detailed LCA

the baseline LCA elaborated in this Guide, complying with the ISO 1404X standards and representative of studies typically requiring between 20 and 200 person-days of work.

difference analysis

a type of LCA focusing on the differences between two alternative product systems, thus ignoring those unit processes that are qualitatively and quantitatively identical.

economic flow

a flow of goods, materials, services, energy or waste from one unit process to another; with either a positive (e.g. steel, transportation) or zero/negative (e.g. waste) economic value.

economic process

→ unit process

economy-environment boundary

see also: system boundary

elementary flow\*

matter or energy entering or leaving the product system under study that has been extracted from the environment without previous human transformation (e.g. timber, water, iron ore, coal) or is emitted or discarded into the environment without subsequent human transformation (e.g. CO2 or noise emissions, wastes discarded in nature)

see also: environmental intervention

emission

a chemical or physical discharge (of a substance, heat, noise, etc.) into the environment, considered as an environmental intervention.

endpoint

→ category endpoint

endpoint approach

→ damage approach

environment system

the natural environment and its constituent processes.

environmental effect

→ environmental impact

environmental impact

a consequence of an environmental intervention in the environment system.

environmental intervention

a human intervention in the environment, either physical, chemical or biological; in particular resource extraction, emissions (incl. noise and heat) and land use; the term is thus broader than (‘elementary flow’).

environmental life cycle assessment \*

→ life cycle assessment

environmental mechanism \*

for a given impact category, the chain of environmental processes linking

interventions to impacts; modeled in LCA (usually only partially) to one or more category endpoints by means of a characterisation model.

environmental process

a physical, chemical or biological process in the environment system that is identified as part of the causal chain linking a particular environmental intervention to a particular impact, e.g. pollution leaching or bioaccumulation; for a given impact category, the environmental processes together form the environmental mechanism.

environmental profile

the overall result of the characterisation step: a table showing the indicator results for all the predefined impact categories, supplemented by any other relevant information.

environmental relevance \*

the degree of linkage between a category indicator and category endpoint

expert review\*

→ critical review

extraction

withdrawal of a biotic or abiotic resource from the environment in a unit process, considered as an environmental intervention.

final product

a product requiring no additional transformation prior to use

flow diagram

a graphic representation of the interlinked unit processes comprising the product system.

foreground system/process

a system or process for which primary, site-specific data are used in an LCA, for whatever reason.

format

a structured framework for representing and possibly processing unit process data as well as any relevant remarks.

function

a service provided by a product system or unit process

functional flow

any of the flows of a unit process that constitute its goal, viz. the product outflows of a production process and the waste inflows of a waste treatment process.

functional unit\*

the quantified function provided by the product system(s) under study, for use as a reference basis in an LCA, e.g. 1000 hours of light (adapted from ISO).

goal and scope definition \*

the first phase of an LCA, establishing the aim of the intended study, the functional unit, the reference flow, the product system(s) under study and the breadth and depth of the study in relation to this aim.

grouping \*

a step of Impact assessment in which impact categories are aggregated in one or more sets defined in the Goal and scope definition phase; it may take the form of sorting and/or ranking.

impact assessment \*

the third phase of an LCA, concerned with understanding and evaluating the magnitude and significance of the potential environmental impacts of the product system(s) under study.

impact category \*

a class representing environmental issues of concern to which environmental interventions are assigned, e.g. climate change, loss of biodiversity

impact score

→ indicator result

indicator result \*

the numerical result of the characterisation step for a particular impact category, e.g. 12 kg CO2-equivalents for climate change.

inflow

→ input

input

a product (goods, materials, energy and services), waste for treatment or environmental intervention (including resource extraction, land use, etc.) modeled as ‘entering’ a unit process (adapted from ISO)

interested party

→ stakeholder

intermediate product \*

An input or output from a unit process which undergoes further transformation before consumptive use.

interpretation \*

the fourth phase of an LCA, in which the results of the Inventory analysis and/or Impact assessment are interpreted in the light of the Goal and scope definition (e.g. by means of contribution, perturbation and uncertainty analysis, comparison with other studies) in order to draw up conclusions and recommendations.

intervention

→ environmental intervention

inventory analysis \*

the second phase of an LCA, in which the relevant inputs and outputs of the product system(s) under study throughout the life cycle are, as far as possible, compiled and quantified.

inventory table

the result of the Inventory analysis phase: a table showing all the environmental interventions associated with a product system, supplemented by any other relevant information (adapted from ISO).

land occupation

the unavailability of a given plot of land for alternative uses for a certain period of time.

land transformation

the change in the quality of a given plot of land due to a particular mode of human use, measured in terms of changes in biodiversity and life support functions.

LCA process

the integral series of exchanges among the individuals and organisations participating in an LCA project, from project initiation and guidance through to interpretation and discussion of the results.

LCA project

A project that seeks to obtain particular results by means of an LCA study and LCA process; besides commissioning parties and practitioners, it may also involve other organizations and individuals, in the capacity of data supplier, peer reviewer or interest group, for example.

LCA study

An environmental study in which LCA methodology is employed, performed by

practitioners who may or may not be affiliated to the party or parties commissioning the study.

life cycle \*

The consecutive, interlinked stages of a product system, from raw materials acquisition or natural resource extraction through to final waste disposal.

life cycle assessment (LCA)

Compilation and evaluation of the inputs, outputs and potential environmental impacts of a product system throughout its life cycle; the term may refer to either a procedural method or a specific study.

life cycle impact assessment \*

→ impact assessment

life cycle impact category indicator \*

→ category indicator

life cycle interpretation \*

→ interpretation

life cycle inventory analysis \*

→ inventory analysis

life cycle inventory analysis result \*

→ inventory table

life support functions

the ecological structures and processes that sustain the productivity, adaptability and capacity for renewal of lands, water and/or the biosphere as a whole.

marginal modeling

a type of modeling whereby changes in inputs and outputs are modeled on a marginal basis (e.g. full attribution to one additional train passenger of the extra power consumption required for transporting that passenger). Note: use of the word marginal is sometimes ambiguous; see section 1.2.3.4 of Part 3 for more details.

midpoint approach

→ problem-oriented approachengroMerijn Tinga

a unit process yielding more than one functional flow, e.g. co-production, combined waste processing, recycling.

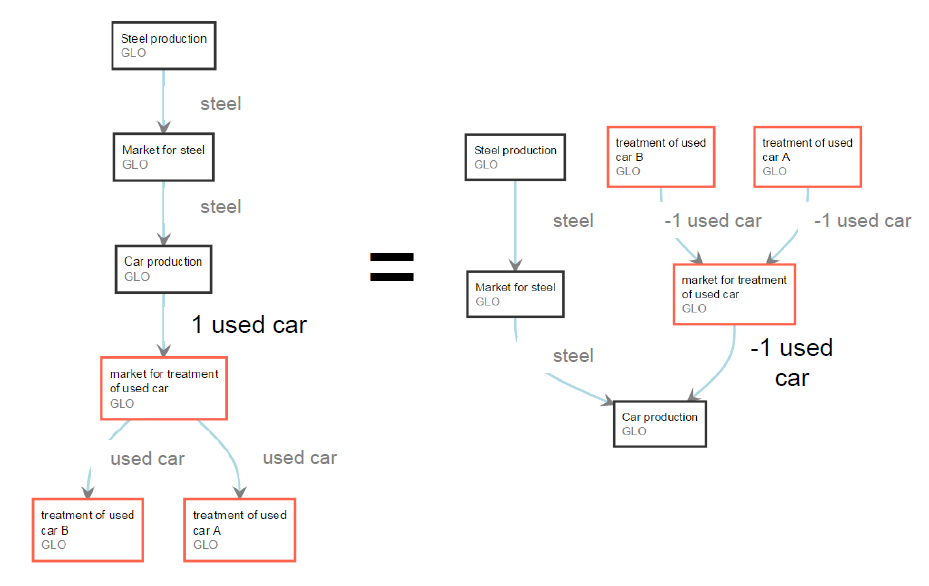

multifunctionality and allocation \*

a step of the Inventory analysis in which the inventory model is refined and the input and output flows of multifunctional processes are partitioned to the functional flows of those processes.

natural resource

a biotic or abiotic resource that can be extracted from the environment in a unit process.

non-functional flow

any of the flows of a unit process that are not the goal of that process, viz. product inflows, waste outflows and environmental interventions.

normalisation \*

a step of Impact assessment in which the indicator results are expressed relative to well-defined reference information, e.g. relative to the indicator results for global interventions in 1995.

normalisation factor

the reciprocal of the indicator result for a particular impact category and reference system; used in the normalisation step.

normalisation result

→ normalised environmental profile

normalised environmental profile

the result of the normalisation step: a table showing the normalised indicator results for all the selected impact categories, supplemented by any other relevant information.

normalised indicator result

the numerical result of normalisation for a particular impact category, e.g. 0.02 yr for climate change.

open loop recycling \*

Recycling of material generated in one product system in a different product system.

optional extension

an option for enhancing the quality of a detailed LCA to address any obvious shortcomings.

outflow

→ output

output

an economic flow (e.g. energy, waste for treatment) or environmental intervention (e.g. pollutant or noise emission) modeled as ‘leaving’ a unit process (adapted from ISO)

perturbation analysis /ˌpɜːtəˈbeɪʃən/

a step of the Interpretation phase to identify any process data in which minor changes may significantly alter the inventory table, the (normalised) environmental profile or the weighting result, to identify efficient options for product improvement or to focus attention on sensitive items.

phase

any of the four basic elements of an LCA, viz. Goal and scope definition, Inventory analysis, Impact assessment and Interpretation.

pollution

a change in the state of the environment due to emissions.

practitioner \*

an individual group or organisation conducting an LCA.

primary function

the main function delivered by the product system under study.

problem-oriented approach

definition of category indicators close to environmental interventions.

procedure

the rules and arrangements adopted to manage an LCA study.

process

→ unit process

see also: environmental process

product

a positively valued economic flow of goods, materials, energy or services produced in a unit process and possibly serving as an input to another unit process.

product system \*

a set of unit processes interlinked by material, energy, product, waste or service flows and performing one or more defined functions.

proportional modeling

a type of modeling whereby changes in inputs and outputs are modeled proportionally (e.g. equal attribution to all passengers of the increase in power consumption needed for transporting one additional passenger). Note: use of the word proportional (and average) is sometimes ambiguous; see section 1.2.3.4 of Part 3 for more details

prospective LCA

→ change-oriented LCA

ranking \*

a grouping method whereby impact categories are hierarchically ranked (e.g. high, medium, and low priority), applying value choices.

recycling

a unit process, or set of processes, for collecting and/or treating waste from a unit process for useful application in the same or in a different product system (closed and open loop recycling, respectively).

reference flow

quantified flow generally connected to the use phase of a product system and representing one way (i.e. by a specific product alternative) of obtaining the functional unit.

release

→ emission

retrospective LCA

→ descriptive LCA

sensitivity and uncertainty analysis

a step of the Interpretation phase to assess the robustness of the overall LCA results with respect to variations and uncertainties in the methods and data used.

sensitivity check \*

an ISO step included in this Guide as part of sensitivity and uncertainty analysis.

simplified LCA

a simplified variety of detailed LCA conducted according to guidelines not in full compliance with the ISO 1404X standards and representative of studies typically requiring from 1 to 20 person-days of work.

sorting \*

a grouping method whereby impact categories are sorted on a nominal basis, e.g. by characteristics such as emissions and resource use, or global, regional and local spatial scales.

stakeholder \*

an individual group or organisation concerned about or affected by the environmental performance of a product system or the outcome of an LCA. Note: the LCA commissioner is also a stakeholder.

step

a discrete element of any of the four phases of an LCA; some steps (e.g. data format, calculation method) are areas of concern rather than actions.

subcategory

a subdivision of an impact category, e.g. freshwater aquatic ecotoxicity as a subcategory of ecotoxicity.

system boundary \*

the interface between a product system and the environment system or other product systems.

third party \*

a critical reviewer or a stakeholder other than the LCA commissioner or practitioner.

transparency \*

open, comprehensive and understandable presentation of information.

unit process \*

the smallest portion of a product system for which data are collected in an LCA.

use process

a unit process in which the final product is consumed, thereby delivering the function under study.

waste (for treatment)

An economic flow with a zero or negative value produced in a unit process and serving as an input to another unit process (note: materials such as waste paper and scrap metals with a positive economic, i.e. market value are thus not wastes but products) (adapted from ISO).

weighting \*

a step of Impact assessment in which the (normalised) indicator results for each impact category assessed are assigned numerical factors according to their relative importance, multiplied by these factors and possibly aggregated; weighting is based on value-choices (e.g. monetary values, standards, expert panel).

weighting factor

a factor obtained with a weighting method and used to express a particular (normalised) indicator result in terms of the common unit of the weighting result.

weighting profile \*

the result of the weighting step: a table showing all the weighting results, supplemented by any other relevant information.

weighting result

the numerical part of the result of weighting and aggregation of all (normalised) indicator results, e.g. 0.08 yr (note: the result may be expressed as more than one numerical value)

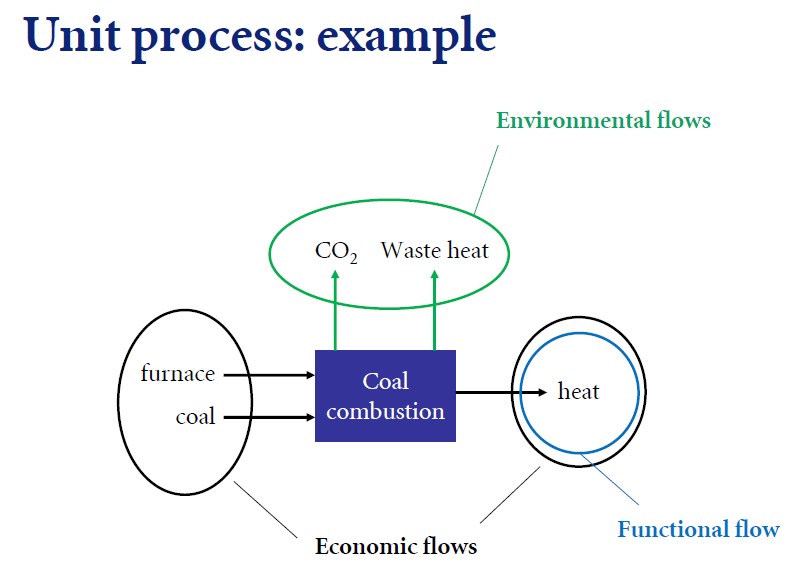

Figure 1: Basic structure of a unit process (or product system) in terms of its inputs and outputs.

Figure 2: Main sequence of phases and steps of an LCA, as set out in this Guide, showing respective results. Phases (in capitals) and steps (lower case) are shown as grey boxes, results as white ‘forms’. The dashed line around ‘weighting’ indicates that this is an optional step which according to ISO 14042 “shall not be used for comparative assertions disclosed to the public”.

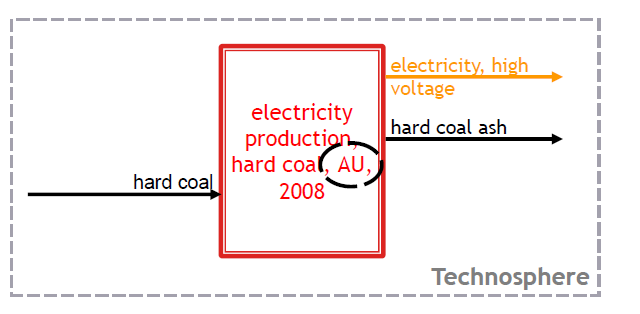

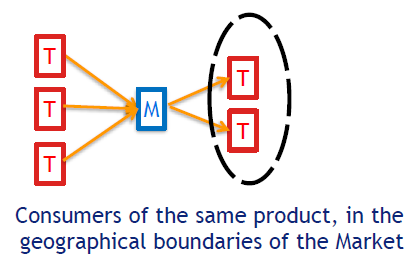

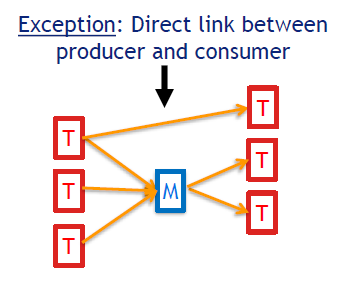

3.2 Flowchart (flow diagram, foreground and background system/process, cut-offs…)

Flow diagram: a graphic representation of the interlinked unit processes comprising the product system.

Foreground system/process: a system or process for which primary, site-specific data are used in an LCA, for whatever reason.

Background system/process: a system or process for which secondary data, viz. databases, public references, estimated data based on input-output analysis, are used in an LCA.

Background processes: can also be depicted with arrows only (thus no boxes); the advantage is that diagrams get less cluttered; the disadvantage that the information on the producing activity is lost; the choice is yours; you do not need to report all inputs from background processes, but only those that are important for your system.

Fore- vs. Background systems: FG is what you model yourself (also when you adapt background processes); background processes are “untouched” from an LCI database.

Environmental flows: While these are part of unit processes, they are typically not shown in flowcharts.

Cut-offs: flows that are not considered in your system are described by entering or leaving the system boundaries. In addition to cut-offs also reference flows and co-products will leave the SB.

Multifunctionality: how co-products are dealt with does not need to be described at the level of the flowchart ( e.g. system expansion vs. allocation), but it is good to indicate such processes.

multifunctional process: a unit process yielding more than one functional flow, e.g. co-production, combined waste processing, recycling.

multifunctionality and allocation *: a step of the Inventory analysis in which the inventory model is refined and the input and output flows of multifunctional processes are partitioned to the functional flows of those processes.

3.3 Unit process

4. Goal and Scope Definition

4.1 ISO, GSD definition, and ALCA vs.CLCA

LCA: ISO definition

Compilation and evaluation of the inputs, outputs and the potential environmental impacts of a product system throughout its life cycle.

Unresolved discussion on 2 modes of LCA:

- attributional LCA (ALCA); impacts of current demand as it is (ceteris paribus) for the FU

- consequential LCA (CLCA); impacts as consequence of a change in demand for the FU

Attributional LCA (ALCA): to provide information on what portion of global burdens can be associated with a specific product life cycle.

Consequential LCA (CLCA): to provide information on the environmental burdens that occur, directly or indirectly, as a consequence of a decision (usually represented by changes in demand for a product).

Source: Section 1.5.2 of “Global Guidance Principles for Life Cycle Assessment Databases” (UNEP 2011)CLCA differs in two ways from ALCA (Weidema, 2003):

- co-product allocation is avoided by system expansion instead of applying allocation factors; and

- included processes are those which are expected to be affected by a change in demand, i.e. processes supplying the marginal product instead of processes supplying the average products used in ALCA models.

See also

Several other modes of LCA exist to model life-cycle impacts of possible future product systems (Guinée et al. 2018)

ALCA & CLCA may show (highly) different results for the same

product system- reason: (scenario-)assumptions !!

“[…] this article compares rapeseed oil and palm oil as a local and a global alternative for meeting the increasing demand for these products in the EU. By using detailed life cycle assessment (LCA), this study compares the environmental impacts and identifies alternative ways of producing rapeseed oil and palm oil to the EU market in order to reduce environmental impacts”. […] “Some, until recently, blind spots in agricultural LCAs are (1) the identification of the marginal/actually affected crops and regions, (2) the identification of how increased demand for an agricultural product is met and (3) avoided environmental interventions from transformation of non-productive land into agricultural land (Schmidt 2008a). Relating to (1), increased demand for rapeseed in the EU may lead to either increased import or increased cultivation or a combination. If cultivation is increased, it is important to clarify if this affects the area cultivated with other crops in the region. For example, in Denmark where the total agricultural area has been declining in the last decades, it is likely that increased cultivation of rapeseed will cause less area available for other crops. Thus, the marginal crop will be displaced. If it is assumed that increased production of rapeseed does not affect the overall food security in the world, the displaced crop will be compensated for in the region representing the marginal supplier of that crop. Relating to (2), it is relevant to clarify if increased agricultural production is met by increased yield or by increased area, i.e. transformation of non-productive land into agricultural land. This may include intermediate crop displacement; e.g. increased rapeseed in Denmark displaces barley; this ‘missing’ barley may be produced in Canada either by intensification or by expanding the agricultural land. […]”

— Source: JH Schmidt Int J Life Cycle Assess(15)2:183–197

4.1 Marginal suppliers of affected crops

…soybean meal as the marginal source of fodder protein and barley as the marginal source of fodder energy…

…the marginal suppliers of soybean meal and barley are Brazil and Canada, respectively.

…When soybean meal is displaced, the output of the dependant coproduct soybean oil is also affected. Market responses to that will most likely be a change in the production of the marginal vegetable oil, i.e. palm oil from Malaysia and Indonesia..

Carrying out the system expansion shows that increased demand for 1 t palm oil requires production of 1.001 t palm oil and the displacement of 2.45 kg soybean meal and 198 kg barley. The additional 0.001 t PO equals the displaced soybean oil which is co-produced with the 2.45 kg displaced soy meal. Correspondingly, increased demand for 1 t rapeseed oil requires the production of the 1 t rapeseed oil and the displacement of 1.045 t soybean meal and 157 kg barley, whilst additional 255 kg palm oil is required.

- However:

- main body of knowledge (“95-99%”) is exactly the same for ALCA and CLCA;

- our conviction that you can only learn and understand CLCA/ALCA if you first have good knowledge on LCA

- there are many more (scenario-based) modes of LCA;

- unclear as yet which questions are more appropriate for different modes of LCA;

- there is no superior approach;

- ……

Read more: Digesting the alphabet soup of LCA

Jeroen B. Guinée

The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment, 2018

Backcasting LCA (BLCA), Decision LCA (DLCA), Integrated LCA (ILCA), Anticipatory LCA (NLCA), Prospective LCA (PLCA), Scenario-based LCA (SLCA).

Table 1 Examples of questions addressed by different modes of LCA

| Question | Reference | |

|---|---|---|

| ALCA | What is the life-cycle impact of 1 kWh of electricity at grid in France in 2006? | (Frischknecht and Stucki 2010) |

| BLCA | What is the maximum attainable affluence for the EU27 in 2020 and 2050 to meet related EU GHG target? | (Heijungs et al. 2014) |

| CLCA | What are the consequences of an increased demand of wheat in Denmark? Which effect does the decision to purchase an additional kWh of electricity have on the electricity market and/or on the environmental impacts? | (Schmidt 2010) (Frischknecht and Stucki 2010) |

| DLCA | Which effect does the decision to purchase an additional kWh of electricity have on the electricity market and/or on the environmental impacts? | (Frischknecht and Stucki 2010) |

| ILCA | What are the system-wide life-cycle impacts of a specific energy transition? | (Hertwich et al. 2014) |

| NLCA | What are the future environmental burdens associated with an emerging technology for both reasonable and extreme-case scenarios? | (Wender et al. 2014) |

| PLCA | What are the environmental benefits and impacts of nanosilver T-shirts compared with conventional T-shirts and T-shirts treated with triclosan? | (Walser et al. 2011) |

| SLCA | What is the best scenario for improving the life-cycle environmental performance of a car? | (Fukushima and Hirao 2002) |

Table 2 Key characteristics of modes of LCA

| Question addressed | Key method | Object of analysis | Scope | Other methods/models used | Allocation method | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temporal | Processes | Data | ||||||

| ALCA | What are the environmental impacts of a product system as it currently functions? | LCA | Commercially existing product system; as it is or was | Present, past | All | SDb | n.a. | Variable |

| BLCA | What is a region’s maximum attainable affluence to meet its planetary boundaries at time t with constant technologies and population? | IOA | Regional/global consumption; as it should be | Future, past | All sectors | Linear programming (LP) simplex algorithm | Variable | |

| CLCA | What are the consequences of an increased demand of a certain product system? | LCA | Commercially existing product system; as it changes due to a decision | Future | Marginal, market | SDb | CGEM; PGEM; IAM; LOM | Substitution |

| DLCA | What are the consequences of an increased demand of a certain product system? | LCA | Commercially existing product system; as it changes due to a decision | Future | Marginal, B2B | SDb | n.a. | Substitution |

| ILCA | What are the global life-cycle impacts of a specific energy transition? | LCA | Global energy consumption | Future | All | SDb and TI, B, IOA | IOA, IEA Blue Map scenario | Variable |

| NLCA | What are the expected environmental impacts of an emerging product system? | LCA | Emerging product system | Future | All | SDb and TI, F, B (optional) | Learning curves; technology and chemical models | Variable |

| PLCA | What are the expected environmental impacts of an emerging product system? | LCA | Emerging product system | Future | All | SDb and TI, F,B (optional) | Learning curves; technology and chemical models | Variable |

| SLCA | What are the expected environmental impacts of a certain future scenario of a product system? | LCA | Emerging product system | Dynamic, from past to future | All | Calculated | Life-cycle modeling language | Variable |

n.a. not applicable; product system (or technology system) a set of unit processes interlinked by material, energy, product, waste, or service flows and performing one or more defined functions (Guinée et al. 2002); SDb standard LCA data(bases), such as ecoinvent, GaBi, ILCD, and USDA; TI assumptions on technical improvements in key energy and material production technologies (Hertwich et al. 2014); F foreground processes; B background processes; CGEM computable and partial general equilibrium model; PGEM partial general equilibrium model; IAM integrated assessment model; LOM linear optimization model; All all processes included for supplying the functional unit; All sectors all industry sectors included for supplying the region’s/global consumption; Marginal processes actually affected by the decision; Market affected processes are determined by using market information and price elasticities; B2B affected processes are determined by factual or anticipated economic business-to-business relationship.

4.2 Goal definition

A hypothetical example:

The goal of the LCA is to identify options for improving the environmental performance of the material polyethylene in throwaway bags for bread. The results of this LCA will be used for product and process development. The plastic bag manufacturer wants to be able to analyse the effects of changes in their processes in terms of technology, inputs, and product composition on the total environmental impact. This information, in turn, can be used to prioritise different measures that can be taken to improve the environmental performance. This LCA does not aim at a public comparative assertion.

The study is performed by Pro-Duct Consultancy Ltd, a moderate-size private engineering bureau. The commissioner is Bag-Away, a large producer of plastic throwaway bags. Interested parties are mainly plastics industry, bakeries and shops. A steering committee with representatives from producer, ministry of environment and academia will be formed. Finally, an expert review will be carried out at NILCAR, the National Institute for LCA Research.

Is LCA the right tool?

What are the environmental impacts of farming fish in Vietnam in the Mekong Delta?

- Risk Assessment rather than LCA …?

What are the environmental impacts related to consuming fish species x cultivated in Viet Nam compared to the same fish species x cultivated in Thailand? - LCA rather than RA …?

4.3 Scope definition

ALCA or CLCA (or LCA)?

Detailed LCA?

Temporal coverage

Geographical coverage

Technology coverage

Coverage of processes

Coverage of interventions and impacts

Function, functional unit, alternatives and reference flows

You should include these Scope elements in your case study report!

- Detailed LCA (LCA Handbook, Part 3, p. 464-467):

- This is not defined by ISO but added in the LCA Handbook (Guinée et al. 2002) to determine the appropriate level of sophistication (simplified, detailed, …) of the LCA study in relation to its goal and application.

- Temporal coverage:

- The desired age of data (e.g. within the last five years) and the minimum length of time over which data should be collected (e.g. one year).

- Geographical coverage

- Geographical area from which data for unit processes should be collected to satisfy the goal of the study (e.g. local, regional, national, continental, global).

- Technology coverage

- Technology mix (e.g. weighted average of the actual process mix, best available technology or worst-operating unit).

- Coverage of economic processes (initial system boundaries):

- “Ideally, the product system should be modeled in such a manner that all the inputs and outputs at its boundary are environmental interventions. It is an iterative process to identify the inputs and outputs that should be traced to the environment, i.e. to identify which unit processes producing the inputs (or which unit processes receiving the outputs) should be included in the product system under study. The initial identification is made using available data. Inputs and outputs should be more fully identified after additional data are collected during the course of the study, and then subjected to a sensitivity analysis.”

- Coverage of elementary flows (environmental interventions) and impact categories:

- “It shall be determined which impact categories, category indicators and characterization models are included within the LCA study. The selection of impact categories, category indicators and characterization models used in the LCIA methodology shall be consistent with the goal of the study”.

- Special case of “coverage of processes”:

- Exclude life cycle stages or subsystems that are qualitatively and quantitatively similar for each of the (product) systems analysed.

- Only if focus is on assessing differences between alternative (product) systems.

- Example: if filling and distribution processes for, e.g., two types of beverage bottles are exactly same.

Scope definition: example

“The LCA is carried out to identify hot spots for improvement of processes in the Netherlands, therefore data should be representative of the present state of technology in that country. In this study, we used the most recent data that were available, mainly from 1999.

We have adopted an attributional approach, which may later be extended to a consequential

approach. For the goal of the study simplified guidelines will suffice for most steps.

Total size of the study is 8 man-months. A large amount of this time will be devoted to the collection of representative data of the most important production, recycling and upgrading processes.”

4.4 Function, functional unit, and reference flow

4.4.1 Function

- A service provided by a product system or unit process, e.g. lighting, transport, enjoying a film, nourishment, etc.

- Or better and more specific: lighting a room of X m2 with light of 1250 lumen

- Etc.

4.4.2 Functional unit

- The quantified function provided by the product system(s) under study for use as a reference basis in an LCA, e.g. 1000 hours of light (of 1250 lumen)

- Adapted from ISO

- Original ISO 14040 definition: “quantified performance of a product system for use as a reference unit”

4.4.3 Generic or strict FU

- The more strictly the functional unit is described, the fewer alternatives will be left to compare …

- The functional unit ‘watching TV for 1 hour’ may be specified to include more and more functions, as in ‘watching colour TV for 1 hour’, ‘watching 55 inch screen

colour TV for 1 hour’, ‘watching 55 inch screen colour TV with remote control for 1

hour’, etc.,

- … until there are no product alternatives left to compare.

4.4.4 Reference flows

- Definition:

- “quantified flow generally connected to the use phase of a product system and representing one way of obtaining the functional unit”

- Ref. flow = FU + specific product alternative supplying FU

- Examples (FU “1000 hours light of 1250 lumen” can be supplied by several different reference flows):

- 1000 hours tube light of 1250 lumen

- 1000 hours fluorescent light of 1250 lumen

- 1000 hours incandescent light of 1250 lumen

- 1000 hours LED light of 1250 lumen

Schematically

focusing on fluorescent and incandescent lamp for reasons of space …

function: lighting a (specific) room

functional unit: 1000 hours of light

alternatives: incandescent lamp and fluorescent lamp

reference flow for system 1: 1000 hours of light with an incandescent lamp

reference flow for system 2: 1000 hours of light with a fluorescent lamp

More examples

Functional unit:

- 1 l of orange juice at the point of sale

Reference flows:

- 1 l of orange juice at the point of sale adopting PEF technology;

- 1 l of orange juice at the point of sale adopting NFC technology;

- 1 l of orange juice at the point of sale adopting FS technology.

Functional unit:

- Colouring 20 m2 of wall type X with opacity 98% and durability of 5 years

Reference flows:

- Colouring 20 m2 of wall type X with

opacity 98% and durability of 5

years using paint A; - Colouring 20 m2 of wall type X with

opacity 98% and durability of 5

years using paint B; - Colouring 20 m2 of wall type X with

opacity 98% and durability of 5

years using paint C.

- Colouring 20 m2 of wall type X with

CMLCA®

- Just for tomorrow afternoon and for your case study:

In CMLCA software the reference flow is the “Alternative”.

Lessons learned

- Provide a ‘function’

- FU = ‘function’ + quantification: don’t forget either one

- Reference flow = FU + alternative

- Define as many separate reference flows as you have alternatives.

- Formulate consistently throughout ‘function’, ‘functional unit’, and ‘reference flows’

The above poses a nice metaphor to some of the existing LCA so far : very exact answers are given to imprecise or vague questions.

5. Exercise on Function, FU, Alternatives and Reference flows

Exercise on Function, FU, Alternatives and Reference flows.

Exercise:

(work in virtual groups or do this exercise on your own for all items listed below):

- What is the function of;

- What is an appropriate FU for;

- What are the alternatives; and

- What are the reference flows for:

5.1 Providing coal-, oil- or wind-based electricity.

Function:

- to provide electricity to the grid

- Energy supply

- Lighting

- ……..

Functional unit:

- to provide elect to 100 Dutch households at peak hr for 1 yr

- to provide 1 kWh electricity to your home … in the night time … ac dc, peak …, efficiency %, in NL/DLD/…,

- kWh

- ……

Alternatives:

- Coal comb/ horizontal wind turb./oil

Reference flows:

- coal to provide elect to 100NL houses at peak hr for 1 yr

- to provide 1 kWh electricity to your home … in the night time … ac/dc, peak …, efficiency %, in NL/DLD/…, by coal power plant; etc.

- Diff of producing lighting from coal/wind/oil

Impact of Coal/oil/wind to produce x kWh

NO! Impact is not the function but the environmental consequence …

- ….

5.2 Using one-way or reusable beverage containers

- Function:

- Containing

1L ofwater - Providing portable liquid

- to supply certain volume of beverage, … in 1.5 litre bottles, … transported from supermarket to your home, …

Contain and maintain milk

- Containing

- Functional unit:

- Containing 1L of water

through distribution system, 10 times - Providing portable liq. 1 week

- 1 liter of beverage transported from supermarket to your home

- 1L milk

- Containing 1L of water

- Alternatives:

- disposable carton container, reusable glass

- Disposable vs reusable

- one-way, reusable

- tetrapak, plasti

- Reference flows:

- containing 1L of water through distribution system for 10times with carton/glass

- containing liq for 1 wk by X, X

- 1 liter of beverage transported from supermarket to your home by cardboard bottle system, …. glass bottle; one-way glass bottle, one-way cardboard bottle, reusable cardboard bottle, reusable glass bottle

- 1L of milk in tetrapak/plastic

5.3 Consuming traditional or organic potatoes

- Function:

- providing a calorific amount of potatoes grown in the NL to the Dutch market

- Consumption of potatoes grown in the NL

- food/nourishment; providing energy; nutritional value; potato tasting food

- Functional unit:

- Providing 500cal of potatoes grown in the NL

- Consumption of 1 serving of potatoes grown in the NL

- to supply 1 kg of potatoes to your home; fulfilling dietary needs of 1 kg of calories; kcalories; recommended daily intake

- Alternatives:

- Organic and traditional

- Reference flows:

- Providing 500cal of organic/traditional potatoes grown in the NL

- Consumption of 1 serving of organic/traditional potatoes grown in the NL

- to supply 1 kg of organically/traditionally cultivated potatoes to your home, … etc.

5.4 Communicating by paper, telephone, or e-mail

Function:

- Transmitting information

- Story telling

- Transmitting data from NL to …

- …..

- Functional unit:

- transmitting information in 1000 words to 1000 people

- to provide story x to person y

- Transmitting 100 kb of data from NL to …

- ….

- Alternatives:

- Email, telephone, paper, sms, ….

- Reference flows:

- Transmitting info in in 1000 words to 1000 people by email/paper/…

- to provide story x to person y by paper/telephone/e-mail (PC, tablet, phone,…)

- Transmitting 100 kb of data from NL to … with telephone/email/paper

- ……

6. Inventory analysis

“Phase of life cycle assessment involving the compilation and quantification of inputs and outputs, for a given product system throughout its life cycle” [ISO 14040]

Steps involved:

- Refining of system boundaries / determination of cut offs

- Drawing a flow chart / product system

- Collecting unit process data

- Dealing with multi functional processes

- Calculating the life cycle inventory analysis result

Goal: to determine the environmental flows related to a

product system (Life Cycle Inventory)

6.1 Economic and environmental flows and the economy environment system boundary

Economic vs. environmental flows

Economic flows: Products, services, and wastes produced and managed by humans. For example: steel, electricity, and wastewater

Environmental flows: 1) Flows entering the product system without prior human transformation , e. land use, freshwater use, metal extraction all resource extraction. 2) Flows leaving the product system without subsequent human transformation , e.g.: emissions (air, soil, water)

6.2 Unit processes

“smallest element considered in the life cycle inventory analysis for which input and output data are quantified”

6.3 Cut-offs

Cut offs and system boundaries

Rule: Each economic input or output of a unit process should be followed until it has been translated into environmental flows ( e.g. resource extractions and emissions)

Examples:

TV -> transformer -> copper wire -> copper -> copper ore

TV -> electricity -> coal, gas, etc.

TV -> electronic equipment waste -> removal of precious and recyclable materials -> dump site -> toxins

The System Boundary is the demarcation between what is included in the product system and what is excluded (cut off).

- Practical constraints: Lack of data, time/funds

- Ignorance: We may not be aware of certain process inputs/outputs

- Predefined criteria

- Purpose/motivation of study or leverage of commissioner: e.g. water flows not included

- Difference analysis: we may leave out certain parts of a system as it is the same for all compared alternatives.

Common system boundaries / cut offs

Example: T shirt

“The principles of system boundary definition are decided during the GSD. However , one may have to wait to decide the exact details until enough information has been collected during inventory analysis”[Hitchhikers guide, page 79]

6.4 Flow diagrams

What is it?

- Simplified graphical representation of a product system

- Showing interdependence of economic processes

Why do we need it?

- Useful for modeling a product system

- Great communication tool showing others what your LCA is about

Constructing a flow diagram is a “cumulative and iterative process with revisions and elaboration as more is learned about the modelled system […]”

[Hitchhikers guide to LCA: p98]

In reality, supply chains are complex ….

Flow diagram checklist

- Show system boundaries

- Unit processes (boxes)

- Economic flows (arrows) No environmental flows

- Distinguish between foreground & background

- Show cutoffs

- Reference flow crossing the system boundary

- Legend

- No numbers

- Is it legible? /ˈledʒəbəl/

6.5 Data collection and reporting

Data Collection

Incremental steps.

Start with main components, THEN add detail.

LCAs require attention to detail AND the bigger picture.

Format and data categories (1)

Central entity in LCA: “Unit process”

General considerations:

- processes have inputs and outputs

- processes have economic flows and environmental/elementary flows

- several types of each (e.g., materials, energy, atmospheric emissions)

- symmetry in economic flows (output of one process is input of another process)

Unit process

“smallest element considered in the life cycle inventory analysis for which input and output data are quantified”

Data sources

Primary data:

- measurements

- stoichiometric calculation /ˌstɔikiə’metrik/化学当量的;化学计算的

- expert interviews

Secondary data:

- (scientific) literature

- reports

- LCI databases for basic processes and materials (e.g. ecoinvent)

What if we don’t have primary /

secondary data?

Possible solutions:

- Background (database)

- Provide estimations Proxies

- Omitting mass flows < 1 or 5%, (but check if they could be environmentally relevant, e.g. rare earths)

i.e. Cut off certain flows (Last resource OK as starting point). Report the influence/existence/justification of cut offs.

molecular /məˈlekjələ $ -ər/, stoichiometry/ˌstɒɪkɪ’ɒmɪtrɪ/ n. 化学计算(法);化学计量学

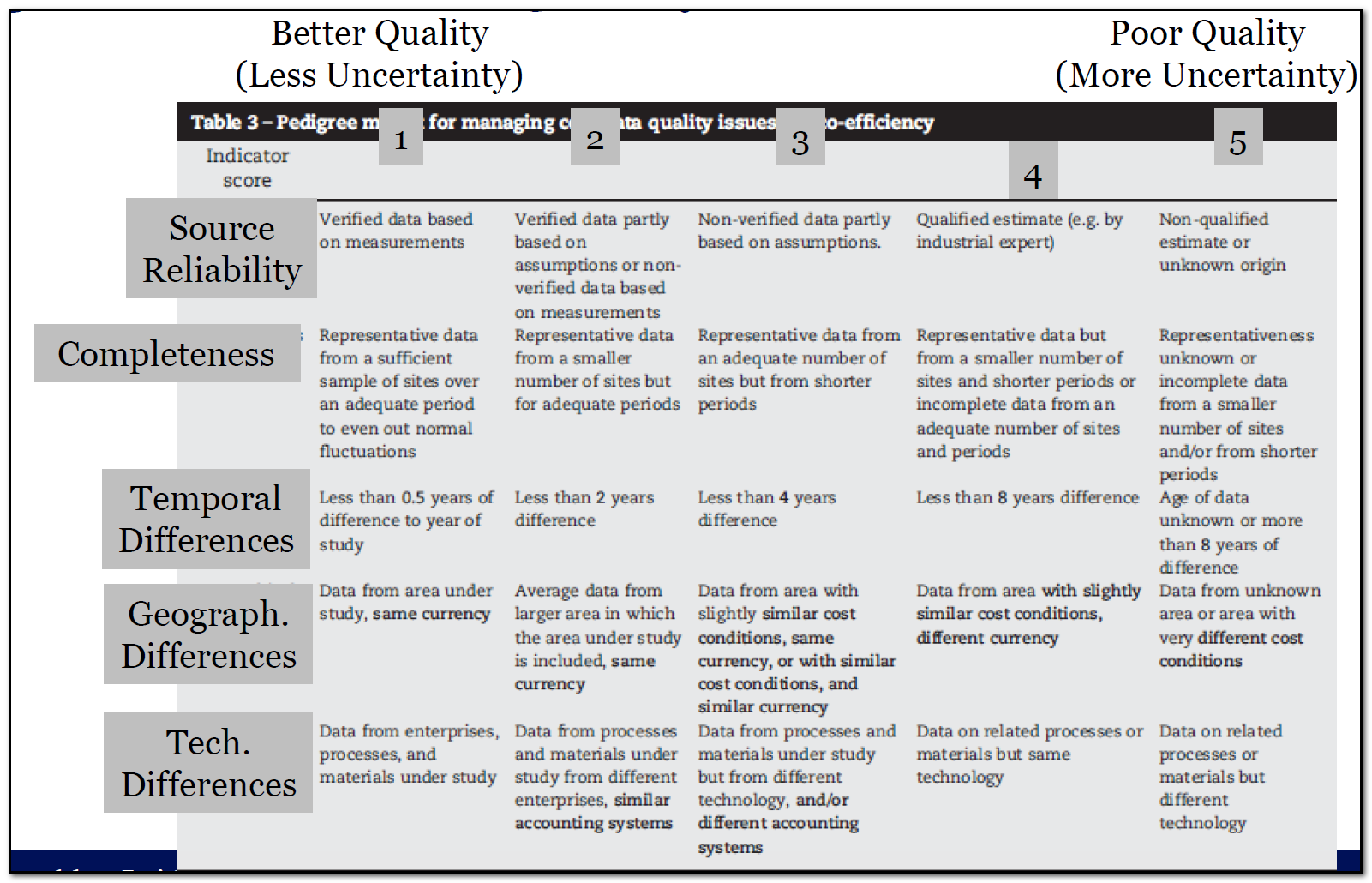

Data quality

Crucial to address data quality

- precision

- completeness

- representativeness (temporal, geographical, technology)

- consistency

- reproducibility

No standardised method for overall assessment of data

quality available (Pedigree matrix used in ecoinvent to quantify uncertainty /‘pedɪgriː/).

- Report: Assumptions, Calculations (equations, units), and Modifications to database.

- Keep a logbook/ Excel (reproducible results).

Unit process data reporting

Example

Best report unit process data similar to this. One table per unit process you model (either in Inventory Analysis section or Appendix of your report).

Inventory table (or LCI = life cycle inventory)

List of all physical interactions between a product system and the environment.

Calculation of LCI analysis results

Relating unit processes to reference flow(s)

- Based on linear scaling of processes

You never need to scale your product system manually! The computer does this for you…

- Matrix algebra solution available

- Take account for (feedback) loops

Calculation only works, if:

- One unique supplier for every product

- Multi functionality is resolved

6.6 Data pitfalls

- Errors are easily introduced …

- errors in measurements

- errors in data entry

- errors with units (litre versus gallon)

- errors with prefixes (mg versus mcg)

- errors with nomenclature (N2O versus NO2)

- … and can sometimes easily be detected

- comparative analysis of different data sources

- mass and energy balances

- Recycling

Missing data: blank, “99”, “0”, “#N/A”.

Notation: thousands separator, keyboard settings.

Units: SI units (m, kg, s, K)

Prefixes:

Significant digits : don’t claim to be more precise than you are able to

6.7 Exercise

Function: providing electricity

Functional unit: producing 1kWh of electricity

Alternatives: coal, oil and wind

Resource flows: producing 1kWh of electricity from oil

producing 1kWh of electricity from coal

producing 1kWh of electricity from wind

could include proper specification low Vol etc, location, (temporal scope), seasonal specification

Function: packaging beverage => contain and maintain beverage

Functional unit: packaging 1 litre of X

Alternatives: reusable beverage container, one-way beverage containers

Resource flows: packaging 1 litre of X in a reusable container

Packaging 1 litre of X in a one-way container

Packaging here is very specific -> what is the function? Containing instead!

Function: consumption of potatoes grown in the NL

Functional unit: consumption of 1kg of potatoes grown in the NL

Alternatives: organic, traditional

Resource flows:

Function: exchanging information

Functional unit: 500 words of information to 1000 people for a specific distance? Instant paper? Then what about paper?

Alternatives: email, telephone, paper, sms

Resource flows: transmitting info in 500 words to 1000 people by email/…

A. What would be an appropriate function and functional unit for a comparison involving more types of lighting options?

Function: lighting

Functional unit: 1000 hours of lighting

B. Define the appropriate (more appropriate than the working-definition provided below) reference flow based on your functional unit for the system depicted above.

Resource flow: 1000 hours of lighting with light of 450 lumen LED light bulb in NL.

C. Redraw the process flow diagram, while omitting the ‘Glass manufacturing’ and ‘Waste disposal’ processes and without connecting to other processes (!!). Do this by drawing the remaining 3 processes as rectangles, then draw the arrows for inflows and outflow for each of the 3 processes (economic flows in vertical direction; environmental flows in horizontal direction) according to the specifications in the above table (but, as said, without connecting to other processes!!). Then insert the quantitative data from the table above next to each of the flows.

| Product | Outflow | Energy content (GJ) | Allocation factor F1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electric power | 500 kWh | 2 | 0.4 |

| Steam | 1000 kg | 3 | 0.6 |

| Total | 1 |

Electric power 4MJ/kWh electric power

Steam 3 MJ/kg steam

| Environmental outflow | unit | Quantity allocated to 500 kWh | electric power Quantity allocated to 1000 kg steam |

|---|---|---|---|

| CO2 | Kg | 400*0.4 = 160 | 240 |

| CH4 | Kg | 6*0.4 = 2.4 | 3.6 |

| N2O | Kg | 0.005*0.4 = 0.002 | 0.003 |

F. Now redraw the process flow diagram from assignment C, replacing the quantitative process data for ‘Power generation (using Cogeneration)’ by the quantities you have allocated to 500 kWh electric power in assignment E.

G. Calculate the scaling factors for the 3 processes. Scaling factors represent the fraction of the process that is needed to fulfil the functional unit defined. Note that you should use the flow diagram you drew in assignment F (including process data of the first Table) to determine how the scaling factor for the process of ‘Using the light bulb’ affects the other processes. Start from the functional unit, determining the reference flow from the use process, etc.

H. Fill in the ‘inventory table’ below. Inventory table for 1000 hours of light (from a 450 Lumen LED light bulb)

I. You can calculate the ‘climate change indicator’ result by multiplying the greenhouse gas emissions by their respective GWPs. Fill in the result in the table below.

J. Which emission from which process contributes most to the result for the climate change indicator?

CO2 emissions from power production

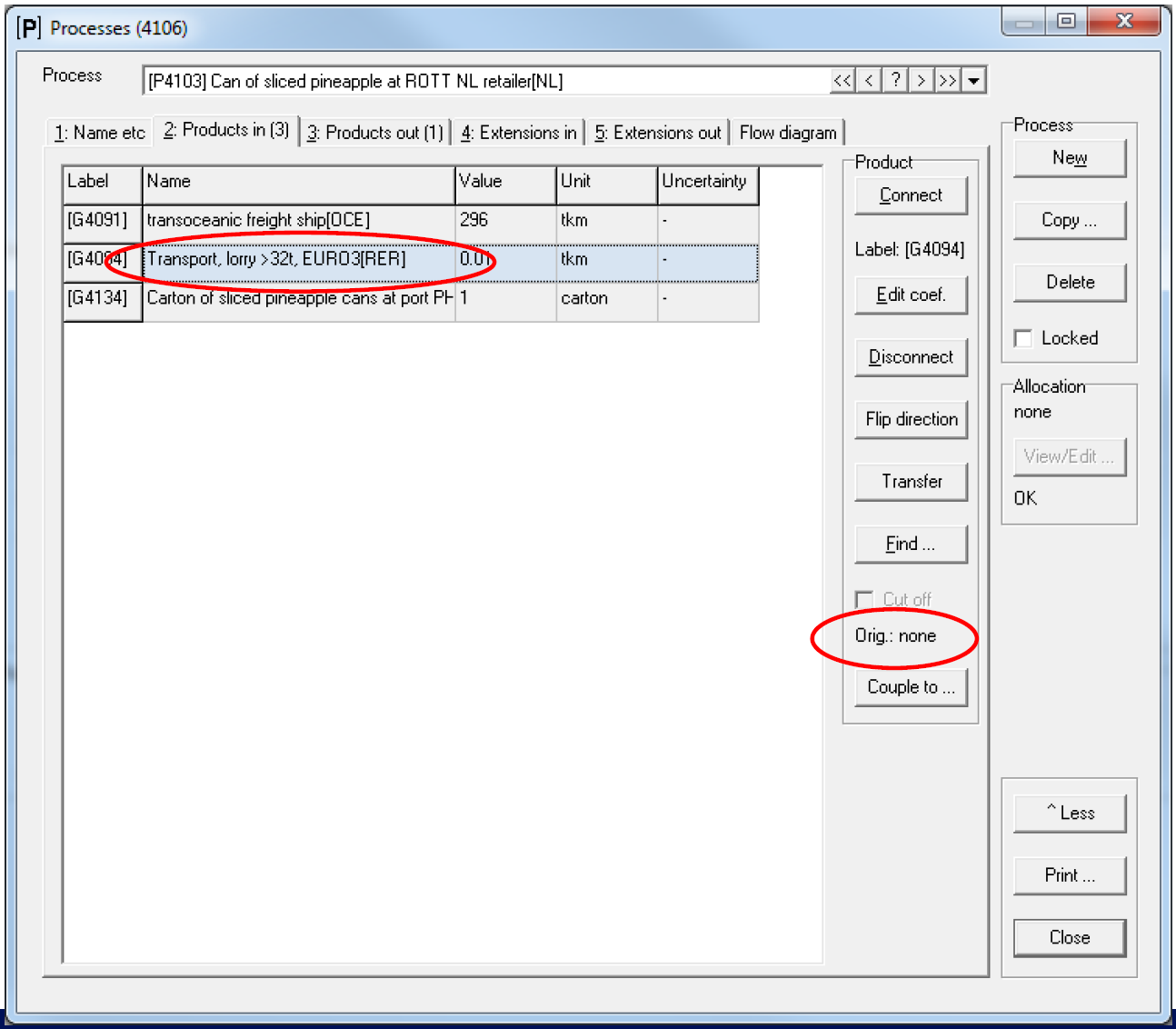

7. CMLCA introduction

7.1 Introduction to CMLCA software

CMLCA and corresponding documentation is available at our separate www.cmlca.eu website. For the LCA-PR course we use the CMLCA version that is available through the Blackboard page of the course.

On the other hand, it is developed with the principles of LCA, IOA, etc. in mind, so that it is quite accurate and up-to-date as to methodological details. It is, for example, fully based on matrix algebra, although the user may be unaware of that whilst using the program. This implies that process trees with a recursive flow structures (steel production needing coal and coal production needing steel), provide no computational problems and are exactly solved. Moreover, the program is very flexible in dealing with allocation of multiple processes. In contrast with some other programs, such processes need not be allocated prior to their entry in the database, and the allocation method (substitution, partitioning, or no allocation at all) may be defined for each individual unit process. The program also supports fully hybrid inventories, consisting of process-based and IO-based data. It is rich in its analytical possibilities.

7.2 Exercises using CMLCA and ecoinvent

CMLCA: Scientific software for LCA, IOA, EIOA and more

- Intended to support the technical steps of LCA

- Doesn’t support procedural aspects, like peer review, etc.

- Assumption: user is aware of basic LCA principles

- Just one of many software tools that are available

- Its philosophy is probably somewhat different

- The program develops continuously

- Available through the MST “CMLCA download” channel

and http://cmlca.eu/cmlca61.zip- Also see the CMLCA pdf file in the same channel for more info

7.3 7 reasons for using CMLCA

- free

- flexible

- perfect for use in class room

- perfect for use by scientists

- compatible with ISO framework and terminology

- does not require an administrator for installation & can be transferred online

- Advanced settings

7.4 7 reasons for not using CMLCA

- has no helpdesk

- contains no process data (but we will import ecoinvent)

- contains no impact assessment data (“but we will import these with you”)

- not so good for consultants

- no graphical interface for constructing flow diagrams

- only available in English

- only available for Windows (!!) (but there is a CMLCA-FAQ including “Mac-problems” in the MST “CMLCA download” channel; see “CMLCA Troubleshooting and FAQs.pdf” )

8. Case study brainstorm session and topics database

8.1 Reflect on a possible topic

Given the case study requirements, think of a topic (either your own or from the list of previous topics) and elaborate, briefly:

- Establish relevance. Why should we care about the topic?

- Justify the use of LCA for the case study. Why is it necessary to evaluate life cycles?

- What’s the comparison

Helpful to think about the following when selecting a topic

- WHY: Relevance and LCA justification

- HOW: How you may approach this (scope)

- WHAT: what may you obtain from results

- Single use vs reusable

- Bio vs fossil

- Local vs foreign

- … others?

- Make sure to involve a comparison

- Keep it simple; learning LCA is already challenging enough!

For example: cloud vs HD storage, Spotify vs CDs, is too abstract and lacks clear boundaries (e.g., what is the Spotify system and where does it stop? Before you know you need to model all servers behind this system which is practically not feasible)

- Do select an ‘easy topic’!

- Don’t do an LCA on a waste management system: too

complex!! - Don’t do a case for a commissioner:

- you won’t often get the data needed, even when ‘promised’ …..

- LCA-PR case study results are too uncertain

- the course is about learning LCA, and that’s already challenging enough.

8.2 Previous case-study topics

- Almond vs Dairy milk

- Bamboo vs oak flooring

- Plastic bags or a lunchbox for your lunch

- Closed- vs open-loop hydroponics

- Using pig manure to power pig farms in Taiwan

- E-reader vs paper book

- Importing tomatoes from Spain or growing in NL

- Olive oil production in Turkey or Greece?

- Waste management options in Bangladesh

- Plastic bottles vs cans

- Newspaper waste management

- Using cotton or nylon for clothing

- Led bulbs vs incandescent bulbs

- Couscous vs Quinoa

- Genuine vs synthetic leather

- Sheep wool vs acrylic wool

- Fresh vs canned pineapple

- Honey vs sugar as a sweetener

- Textile dying with supercritical CO2

- Filter drip vs instant coffee

- Clay bricks vs sand-lime bricks

- Copper telluride production

- Cooking on gas or cooking on electricity

- Beer vs wine

- Bio-composites

- Plastic vs metal cutlery

- LCA of textiles: cotton vs. nylon /’naɪlɒn/

- 2nd Generation Nest Learning Thermostat and the Honeywell Round CT-87N /ˈθɜːməstæt/

- a cup of filter drip coffee compared to a cup of freeze dried instant coffee

- Advancing sustainable urban farming: a comparative LCA of aquaponics vs. aeroponics

- Almond Milk or Dairy Milk /‘ɑːmənd//‘deərɪ/

- animal feed from food waste as compared to producing animal feed from grains

- Are glasses more sustainable or contact lenses, a case study of LCA

- Ballpoint pen versus fountain pen

- bamboo versus cotton clothing

- Beef and Chicken Meat in the Netherlands

- beef burger and a soy based burger

- biodiesel production from two available feedstocks in Mexico: CLORELLA VULGARIS & JATROPHA CURCAS

- Bottled versus tapped water at festivals

- Butter and Margarine

- BUTTER versus olive oil for frying

- cashew nuts and chicken fillet /‘kæʃuː/

- Cement production

- Ceramic mug compared to a plastic cup /sɪ’ræmɪk/

- Ceramic plates or paper plates?

- Chicken vs Mealworm protein production

- Chalkboard vs. whiteboard

- clay brick or sand-lime brick in Indonesia

- Horticulture tomatoes in the Netherlands

- Cocaine Production in Colombia to supply for the European Market

- Colombian bananas: Organic vs. Conventional Production systems

- Comparative LCA of copper telluride production

- Comparative LCA on constructing a tower from ABS LEGO bricks vs. cherry wooden Eco-Bricks

- Comparative LCA study of wooden and cellulose-acetate spectacle frames

- Comparative Life Cycle Assessment of NiMH and Li-Ion Batteries in Electric Vehicles

- Comparative life cycle assessment of two steak dinner alternatives

- Comparing Capsule, Pod and Drip Filter Coffee

- comparison of microalgae culture coupled to biodiesel and biogas production

- Concrete and asphalt pavements /‘æsfɔlt/沥青

- Conventional versus organic beef

- Conventional versus organic milk