The evolution of life cycle assessment in European policies over three decades

The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment

Serenella Sala, Andrea Martino Amadei, Antoine Beylot & Fulvio Ardente

$^{1}$ European Commission - Joint Research Centre, Ispra, VA, Italy

$^{2}$ BRGM - Bureau de Recherches Géologiques et Minières, Orléans Cedex 2, France

Table of Contents

Introduction

- Life cycle thinking (LCT) is the basic concept assessing burdens adopting a holistic perspective, from raw material extraction to end of life.

- Whether consequential or attributional fit better the purposes as in Vázquez-Rowe et al. (2014) or Brander et al. (2008).

- The Thematic Strategy on the Prevention and Recycling of Waste (2005) introduce LCT for assessing environmental impacts of the generation and management of waste.

- The Ecodesign Directive was the first to introduce mandatory requirements for new products following on a life cycle approach.

- The 2013 communication “Building the Single Market for Green Products” was a milestone, which established the Product- and Organisation- Environmental Footprint methods( PEF and OEF).

- Recent policies and communications related to LCT and LCA focusing on sectors like packaging, packaging waste, vehicles, plastics (the European Green Deal (2020), the Circular Economy Action Plan (2020), and the Farm to Fork Strategy (2020))

Methods

- A review of current European Union (EU) legal acts and communications explicitly mentioning LCT, LCA, life cycle costing (LCC), and environmental footprint (the European Product and Organisation Environmental Footprint PEF/OEF) is performed, considering the timeframe from 1990 to 2020.

- Documents are categorised by year and types (e.g. regulations, directives, communications (proposals, reports, white papers, and green papers)) and based on their covered sectors (e.g. waste, energy, buildings).

Results

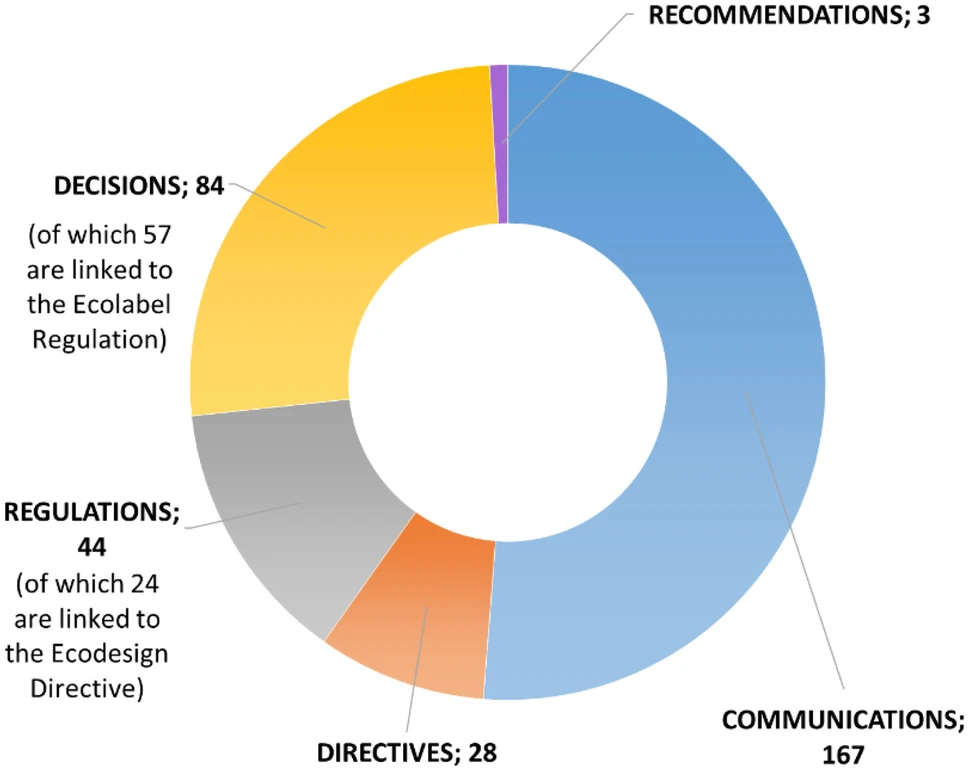

- Communications constitute the main type of documents, followed by decisions and regulations.

- Most of the classified decisions are linked to the Ecolabel Regulation (EC 2010a), whilst most of the classified regulations are linked to the implementation of the Ecodesign Directive (EC 2009a).

Evolution of the implementation of LCT, LCA, LCC, and PEF/OEF in policies and communications - The directive (EC 2019b) defined measures to reduce life cycle environmental impacts of single-use plastics, although no further detailed information was reported on how to perform these assessments.

Discussion

- Both the waste and the construction sector are highlighted as LCA and LCC exhibit particular relevance.

- LCC was especially mentioned in public procurement or in the construction sector.

- In particular, to grant robustness and verifiability, it is necessary to guarantee availability and quality of LCI (life cycle inventory) data.

- Other methodological and practical issues can also affect the integration of LCA into policies, such as the following:

- The use of a consequential versus attributional LCA (depending on the scope of the policy). So far, consequential LCA concepts have been implemented only to a limited extent. In particular, it is worth mentioning the Renewable Energy Directive REDII (EC 2018b) that accounts for indirect land use change;

- The relationship and integration with other models widely used in policy context (e.g. economic models such as partial equilibrium models or general equilibrium models, or other qualitative/quantitative methods for environmental impact assessment);

- The need of normalization and possibly weighting factors when using impacts assessment methods addressing different impact categories;

- The need of defining benchmarks for evaluating policy options (especially in light of using LCA in some labelling schemes, or to set impacts thresholds beyond which the product is not acceptable in the market).

- The right balance between the following:

- Enhancing the comparability of LCA results (by being very prescriptive in data and methodological choices) versus providing the required flexibility (in order to grant the applicability of the LCA to diverse product groups or sectors);

- Allowing limited assessments for a few impact categories (simplifying the interpretation of the results) versus pushing towards more comprehensive assessments (including a large set of impact categories but more difficult to be assessed jointly);

- Using only very robust life cycle impact assessment methods (e.g. with regard to Global Warming Potential, as the main used in policies) versus extending to methods able to address more impacts (e.g. 16 environmental impacts as recommended by PEF), ensuring their applicability into policies.